Abstract

The advent of open innovation has intensified communication and interaction between scientists and corporations. Crowdsourcing added to this trend. Nowadays research questions can be raised and answered from virtually anywhere on the globe. This chapter provides an overview of the advancements in open innovation and the phenomenon of crowdsourcing as its main tool for accelerating the solution-finding process for a given (not only scientific) problem by incorporating external knowledge, and specifically by including scientists and researchers in the formerly closed but now open systems of innovation processes. We present perspectives on two routes to open innovation and crowdsourcing: either asking for help to find a solution to a scientific question or contributing not only scientific knowledge but also other ideas towards the solution-finding process. Besides explaining forms and platforms for crowdsourcing in the sciences we also point out inherent risks and provide a future outlook for this aspect of (scientific) collaboration.

What is Open Innovation and What is Crowdsourcing?

Nowadays, companies use online co-creation or crowdsourcing widely as a strategic tool in their innovation processes (Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler 2009; Howe 2008). This open innovation process and opening up of the creation process can be transferred to the field of science and research, which is called open science.

Here we see open science on a par with open innovation: both incorporate external knowledge in a research process. One way of doing this is “crowdsourcing”. Companies use open innovation when they cannot afford a research and development department of their own but still need external or technical knowledge, or when they want to establish an interdisciplinary route to problem-solving processes. This can be an interesting working milieu for scientists as their involvement in these open innovation processes may lead to third-party funding.

Firms usually initiate open innovation processes by setting up challenges of their own or using dedicated platforms; participation is often rewarded by incentives. The kinds of problems that crop up in the context of open innovation can be very diverse: Challenges can include anything from a general collection of ideas to finding specific solutions for highly complex tasks. IBM’s “Innovation Jam” (www.collaborationjam.com) or Dell’s “IdeaStorm” (www.ideastorm.com) (Baldwin 2010) quote companies that involve employees of all departments and partners in open innovation as an example. They also interact with external experts, customers and even researchers from universities and other scientific institutions, who do not necessarily belong to the research and development department, in order to pool and evaluate ideas. This concept was introduced by Henry W. Chesbrough (Chesbrough 2003).

Firms tend to favor tried-and-tested solutions and technologies when working on innovations: Lakhani (2006) defined this behavior as local search bias. To his way of thinking, co-creation can be seen as a tool for overcoming the local search bias by making valuable knowledge from outside the organization accessible (Lakhani et al. 2007). Von Hippel names various studies that have shown some favorable impacts that user innovation has on the innovation process (von Hippel 2005).

The advantages of open innovation are not only of interest to companies and firms: it is also becoming increasingly popular with the scientific community in terms of collaboration, co-creation and the acceleration of the solution-finding process (Murray & O’Mahony 2007). In the fields of software development (Gassmann 2006; von Hippel & von Krogh 2012) and drug discovery (Dougherty & Dunne 2011) in particular, scientists have discovered the advantages of open collaboration for their own work: open science—which, for the sake of simplicity, we can define as the inclusion of external experts into a research process.

Most open innovation initiatives do not necessarily address the average Internet user. Often scientists and other specialists from different disciplines are needed: Lakhani et al. (2007) find that the individuals who solve a problem often derive from different fields of interest and thus achieve high quality outcomes.

Open innovation accordingly refers to the inclusion of external experts into a solution-finding process. This process was hitherto thought to be best conducted solely by (internal) experts (Chesbrough 2003). Opening up the solution-finding process is the initial step of using participatory designs to include external knowledge as well as outsourcing the innovation process (Ehn & Kyng, 1987; Schuler & Namioka, 1993). Good ideas can always come from all areas. Special solutions, however, require specialized knowledge and, of course, not every member of the crowd possesses such knowledge (“mass mediocrity”, Tapscott & Williams 2006, p. 16). The intense research on open innovation confirmed this conjecture (Enkel et al. 2009; Laursen & Salter 2006).

Before the term “open innovation” came into existence it was already common for companies to integrate new knowledge gained from research institutes and development departments into their innovation processes (Cooper 1990, 1994; Kline & Rosenberg 1986).

Crowdsourcing refers to the outsourcing of tasks to a crowd that consists of a decentralized, dispersed group of individuals in a knowledge field or area of interest beyond the confines of the given problem, who then work on this task (Friesike et al. 2013). Crowdsourcing is used by businesses, non-profit organizations, government agencies, scientists, artists and individuals: A well-known example is Wikipedia, where people all over the world contribute to the online encyclopedia project. However, there are numerous other ways to use crowdsourcing: On the one hand, the crowd can be activated to vote on certain topics, products or questions (“crowd voting”), or they can also create their own content (“crowd creation”). This input can consist of answering more or less simple questions (such as Yahoo Answers), creating designs or solving highly complex issues, like the design of proteins (which we will revert to further down).

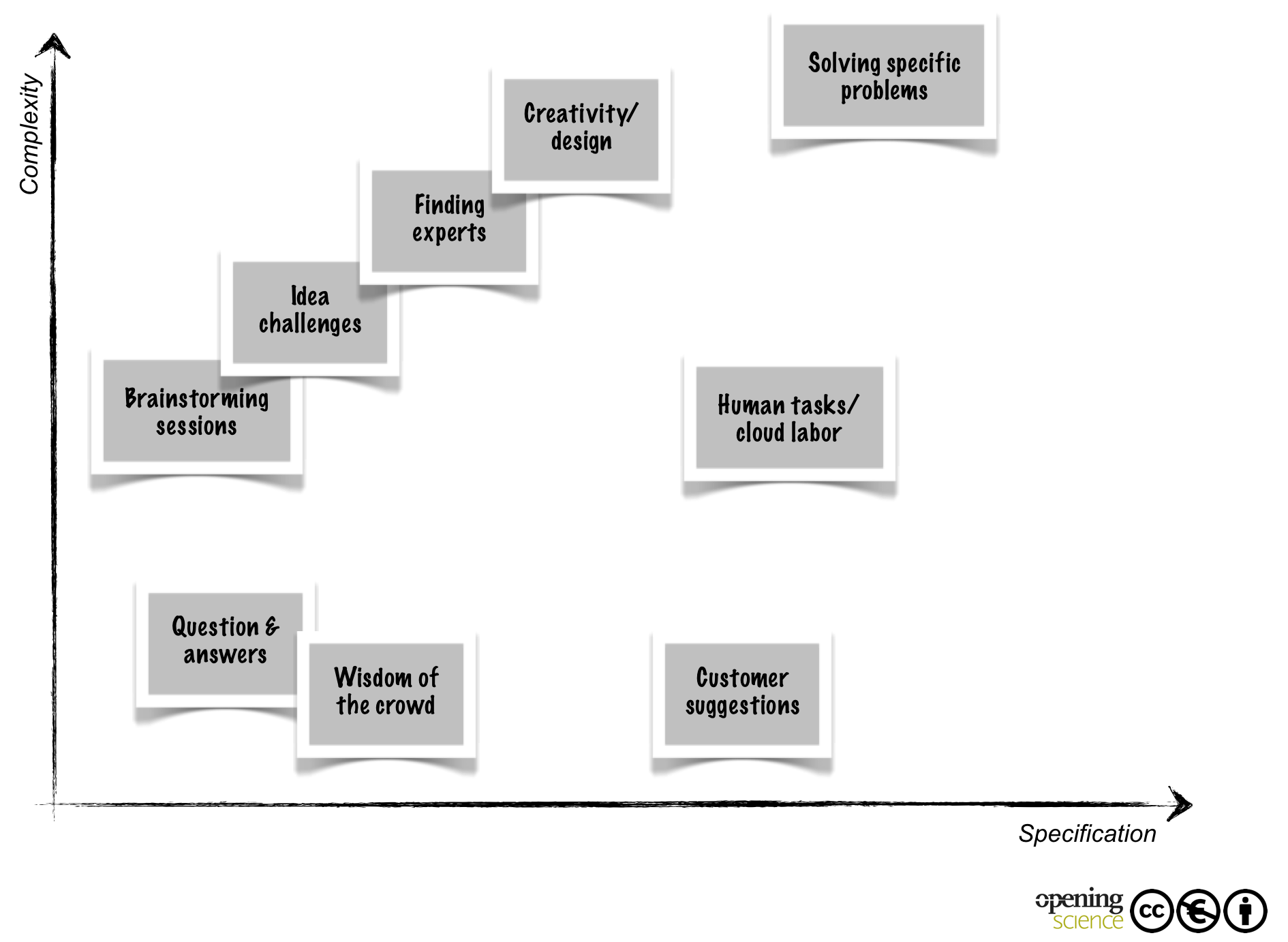

Figure 1 provides an overview of the different aims and tasks of open innovation and crowdsourcing. The position of the varying fields in the diagram mirrors a certain (not necessarily representative) tendency: questions and answers can be fairly complex, a task in design can be easy to solve and human tasks (like Amazon Mechanical Turk) can actually include the entire spectrum from simple “click-working” to solving highly complex assignments.

This section focuses on scientific methods for open science via crowdsourcing, also including possibilities and risks for open innovation and crowdsourcing in the sciences. Two major aspects of online crowd creation via crowdsourcing are firstly being part of a crowd by contributing to a question raised on a crowdsourcing platform and secondly posing a question to be answered by a crowd.

Specialists, scientists in particular, are now the subject of closer inspection: how can scientists and scientific institutions in particular take part in open innovation and open up science projects, and how can they collaborate with companies?

How Scientists Employ Crowdsourcing

The use of crowdsourcing not only makes it possible to pool and aggregate data but also to group and classify data. It would seem, however, that the more specific a task, the more important it becomes to filter specialists out of the participating mass.

Scientists can chose between four main forms of crowdsourcing:

- Scientists can connect to individuals and to interest communities in order to collate data or to run through one or a set of easy tasks, such as measurements.

- Scientists can also use the Internet to communicate with other scientists or research labs with whom they can conduct research into scientific questions on equal terms.

- The second option can also work the other way round: scientists or experts can contribute to scientific questions.

- Options 2. and 3. are frequently chosen by firms and companies as a means of open innovation, often combined with monetary benefits for the participant.

We can conclude that the two major forms of open innovation and crowdsourcing in the sciences are: contributing towards a solution (perspective 1) and requesting a solution (perspective 2).

Perspective 1: Contributing to a Crowdsourcing Process (Open Science)

One form of open innovation through crowdsourcing in the sciences is to contribute to research questions by setting out ideas—often free of charge. In sciences like mathematics and biology or medicine, in particular, open science is a well-known and much appreciated form of scientific collaboration.

One famous example is the U.S. “Human Genome Project”1, which was coordinated by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health. It was completed in 2003, two years ahead of schedule, due to rapid technological advances. The “Human Genome Project” was the first large scientific undertaking to address potential ethical, legal and social issues and implications arising from project data. Another important feature of the project was the federal government’s long-standing dedication to the transfer of technology to the private sector. By granting private companies licences for technologies and awarding grants for innovative research, the project catalyzed the multibillion dollar U.S. biotechnology industry and fostered the development of new medical applications2. This project was so successful that the first, original project spawned a second one: the “encode project”3. The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) launched a public research consortium named ENCODE, the Encyclopedia of DNA elements, in September 2003, to carry out a project for identifying all the functional elements in the human genome sequence4.

Another famous project was proposed by Tim Gowers, Royal Society Research Professor at the Department of Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics at Cambridge University who set up the “polymath project”, a blog where he puts up tricky mathematical questions. Gowers invited his readers to participate in solving the problems. In the case of one problem, it so happened that, 37 days and over 800 posted comments later, Gowers was able to declare the problem as solved.

Collaborating online in the context of open science can be achieved using a multitude of various tools that work for scientists but also for any other researchers: such as a digital workbench, where users can collaborate by means of online tools (network.nature.com); They can also build open and closed communities or workshop groups consisting of worldwide peers by exchanging information and insights (DiagnosticSpeak.com, Openwetware.org); researchers can also establish social networks and pose questions and get them answered by colleagues from all over the world (ResearchGate.com).

Perspective 2: Obtaining Support for One’s Own Science (Citizen Science)

The other aforementioned aspect of open innovation through crowdsourcing in the sciences is to ask a community for help. This aspect refers to Luis von Ahn and his approach to “human computation”: numerous people carry out numerous small tasks (which cannot be solved by computers so far). To ask a community for help works in “citizen science”, which, for the sake of simplicity, we can define as the inclusion of non-experts in a research process, whether it is a matter of data collection or specific problem-solving. Crowdsourcing is a well-known form of “citizen science”. Here, as scientificamerican.com explains, “research often involves teams of scientists collaborating across continents. Now, using the power of the Internet, non-specialists are participating, too.”5

There are various examples where scientists can operate in this manner and obtain solutions by asking the crowd. This form of crowdsourcing is also present in the media: scientific media bodies have established incorporated websites for citizen science projects like http://www.scientificamerican.com/citizen-science where projects are listed and readers are invited to take part. In view of the crowdsourcing strategy “Ask the public for help”, scientists can use these (social) media websites to appeal to the public for participation and help. A research area or assignment might be to make observations in the natural world to count species in the rain forest, underwater or pollinators visiting plants - especially sunflowers, as in The Great Sunflower Project - or to solve puzzles to design proteins, such as in the FoldIt project. Citizens interested in this subject and scientists working in this field of knowledge can therefore be included as contributors.

A very vivid example is the “Galaxy Zoo” project. Briefly, the task is to help classify galaxies. Volunteers are asked to help and it turned out that the classifications http://www.galaxyzoo.org provides are as good as those from professional astronomers. The results are also of use to a large number of researchers.

Another example of how to activate the crowd is ARTigo, a project from art history. A game has been created and each player helps to provide keywords or tags for images. The challenge here is to find more suitable tags—preferably hitherto unnamed ones—than a rivaling player in a given time. The Institute for Art History at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich was accordingly able to collect more than four million tags for its stock of more than 30,000 images6. Paying experts to perform this task would have been unaffordable.

The following examples show how different platforms allow scientists and other experts to engage in open innovation, and how scientists and research departments can use these platforms for their own purposes.

| Innocentive | Innoget | Solution-Xchange | One Billion Minds | Presans | Inpama | Marblar | |

| Country | USA | Spain | India | Germany | France | Germany | UK |

| Founded in | 2001 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2008 | 2012 | 2012 |

| Focus | innovation challenges (initiated by companies/ organisations); community | innovation challenges and presentation of new solutions | innovation challenges; community | scientific and social projects | search for experts on specific issues | completed ideas to date | develop products based on new and existing technologies; gamification |

Innocentive

Innocentive.com is the best known open innovation platform that allows companies and experts to interact (Wessel 2007). It was founded by the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly. According to their own information, there are now more than 260,000 “problem solvers” from nearly 200 countries registered on Innocentive.com. Thanks to strategic (media) partnerships, however, more than 12 million “solvers” can be reached. Over $ 35 million were paid out to winners, with sums ranging between $ 500 and over $ 1 million, depending on the complexity of the task.

Forms of challenges and competitions

Challenges can either be addressed to the external community, or they may be limited to certain groups of people, such as employees. There are also various forms of competitions: “Ideation Challenge”, “Theoretical Challenge”, “RTP Challenge” and “eRFP Challenge”.

- “Ideation Challenges” are for the general brainstorming of ideas - relating to new products, creative solutions to technical problems or marketing ideas, for example. In this case, the solver grants the seeker the non-exclusive rights to his ideas.

- “Theoretical Challenges” represent the next level: ideas are worked out in detail, accompanied by all the information required to decide whether or not the idea can be turned into a finished product or solution. The period of processing is longer than for an “Ideation Challenge”. The financial incentives are also much higher. The solver is usually requested to transfer his intellectual property rights to the seeker.

- “RTP Challenge” calls for a further solution layout on how the solution, once it has been found, can be applied by the company that invited contributions. The “solvers” are accordingly given more time to elaborate the drafts they have submitted, while the reward rises simultaneously. Depending on how the challenge is put, either the intellectual property rights are transferred to the “seeker” or the “seeker” is at least given a licence to use.

- “eRFP Challenge” is the name of the last option to pose a challenge. Scientists in particular might be interested in this option: Normally, companies have already invented a new technology and are now looking for an experienced partner—like external consultants or suppliers—to finalize the developed technology. In this case, legal and financial stipulations are negotiated directly between the cooperating parties.

The site’s “Challenge Center” feature provides an opportunity for interaction between the “seekers” and “solvers”. Companies and institutions—the “seekers”—post their assignments, and the “solvers” select those that are of interest to them based on the discipline in which they work.

Registration, profile and CV

Anybody can register as a “solver”, even anonymously, if they chose, but a valid email address is required. The profile, which is open to the public, can either be left blank or provide substantial personal information. It is possible to name one’s own fields of expertise and interest. There is no strict format for the CV; academic degrees and a list of publications may be mentioned. External links, to one’s own website, for example, or to a social network profile can be added. The “solver” can decide whether he or she wants to make his or her former participations in challenges public. “Solvers” can easily be classified on the basis of this information: the “seeker” obtains an immediate impression of how many “solvers” might have the potential to contribute a solution for the given task. It is also possible to recruit new “solvers”. In this case the “seeker” can observe the activities of the “solvers” involved (under “referrals”). If a successful solution is submitted, the “solver” who recruited his colleague who actually solved the problem gets a premium. The recruitment takes place via a direct linkage to the challenge. This link can be published on an external website or in a social network. The “InnoCentive Anywhere” App creates an opportunity for the “solver” to keep up-to-date with regard to forthcoming challenges.

Innoget

Innoget focuses on linking up organizations that generate innovations with those that are in search of innovation, both having equal rights. Research institutions in particular are addressed as potential solution providers. Solution providers can put forward their proposals for a solution in return for ideas on creating a surplus which might be valuable to them. The basic difference between this and Innocentive.com is that, while Innocentive builds up a community—quite detailed profile information including expertise, subjects of interest and (scientific) background are called for—which makes it possible to form teams to find solutions for a challenge, Innoget.com merely asks for a minimum set of profile questions. It also has to be mentioned that offering solutions/technologies has to be paid for, so Innoget.com seems to be less interesting to individuals than to companies. Participating in and posing challenges is free of charge, although other options have to be remunerated: providing a company profile and starting an anonymous challenge, for instance. Offers and requests are both furnished with tags detailing the branch and knowledge field. You can also look for partners via the detailed search provided. You can choose categories like countries, nature of challenge (such as a collaboration, licensing or a research contract) or organization/institution (major enterprise, public sector, university etc.).

SolutionXchange

SolutionXchange.com was founded by Genpact, an Indian provider of process and technology services that operates worldwide. A distinctive feature is that only Genpact-members and customers can submit challenges to the platform.

As mentioned in the previous examples, registration is easy and free to all experts and users. After naming the most basic information, such as primary domain and industry, it is possible to add detailed information on one’s profile: education, career or social network links etc., but you can opt to dispense with that. As soon as you have registered, you can upload white papers or your own articles or write blog entries that you wish to be discussed. You can also join and found communities. At SolutionXchange.com you can also request to join the network as a pre-existing group or organization.

Ongoing challenges are initially listed according to your profile information; after using filter options, different challenges will be displayed on your profile page as well. Of special interest is the area called “IdeaXchange”, where all the different communities, articles and blogs appear and—independent of the actual challenges—external experts meet Genpact members for discussion. Submitted articles are evaluated by Genpact experts or by the companies that set up the challenge. At the end of the challenge, Genpact has the opportunity to assign individual experts with the task of evolving an idea that was remunerated, depending on the importance or size of the project or the time spent on development.

One Billion Minds

This platform calls itself “Human Innovation Network”; “openness” according to the open innovation principle is highlighted in particular.

Registration is simple, detailed information on one’s profile cannot be named, but you can type in links to your profile located on an external social network.

Inviting contributions towards a given challenge is simple, too: after providing information on the challenger (whoever set up the challenge: company, non-profit organization, individual as well as the origin) only the challenge’s title, a further description of it and a public LinkedIN-profile are required. Afterwards the challenger has to describe the aim of the challenge, possible forms of collaboration between initiator/challenger and participant, a deadline and a description of the rewards (not necessarily monetary rewards). It is also possible to pay for and charge Onebillionminds.com with moderating the submitted answers. At http://Onebillionminds.com social and scientific projects have equal rights to those that have an economical aim. The declared intention of is “to change the world.”7

Presans

Presans.com follows a very different approach from those mentioned above: The company provides a search engine that—according to the platform’s own description—browses through the whole data base that contains about one million experts looking for matching partners. Here Presans.com keeps a low profile when it comes to selection criteria: Nevertheless, it seems that publications and the assurance of the expert’s availability are of value. This issue is based on the assumption that the solution-seeking company often does not know what kind of solution the company is actually looking for.

Inpama

Inpama.com enables inventors and scientists to present their solutions ready for licensing and accordingly ready to be put on the market. Inpama.com was founded by IntentorHaus, a company that runs several inventors’ businesses and inventor or patent platforms in the German-speaking countries. Companies that are looking for solutions can receive information on offers that fit their own business area, so they can easily get in touch with inventors. Impama.com offers inventors various possibilities via different media such as image, text, video or weblinks to describe their products and patents. Tags mark the product’s category. Also, Inpama.com offers further information and assistance with impoving the product or invention by contacting test consumers or industrial property agents or by marketing the invention.

Marblar

Marblar.com adopts a very interesting approach. Assuming that a minimum of 95 per cent of the inventions that have been developed at universities are never realized, scientists should be given a chance to present their inventions to potential financiers and to the public. The special aspect in this instance is for the presented inventions to be developed further through gamification: Players can earn points and can receive monetary rewards up to £ 10,000. In this way, Marblar.com helps to make inventions useful that would have been filed away. Marblar.com also helps to open up a further source of income to the research institutions.

A Landscape of Today’s Platforms: Summary

The crowdsourcing platforms often consist of creatives that participate either by submitting active content, such as contributions to a challenge, or by judging contributions to challenges. Referring to the platform Innocentive.com, where more than 200,000 “problem solvers” are registered, it is obvious that not every single member submits input for every single challenge. Due to the size of the group, however, there is a very great likelihood that a lot of valuable ideas will be put forward. Technically speaking, it is possible that every participant could take part in every challenge, but this is not true of all the platforms mentioned here. Nevertheless, Innocentive.com provides an opportunity of thinking “outside the box” because it allows the participants to name not only their own field of knowledge but also their field of personal interest. It is accordingly possible to generate new ways of solving complex problems. It seems obvious that either communication and interaction within a community or the building of new communities is of interest: the submitted ideas are frequently hidden. It is possible that lots of companies are not as “open” as open innovation suggests, but perhaps concealing ideas is not that absurd after all: these open innovation challenges do not interact with the masses like many other common crowdsourcing projects do. Many crowdsourcing platforms that work in the field of open innovation provide an opportunity for organizing challenges for closed groups or pre-existing communities whose members are either invited, belong to the company or other associated communities that are then sworn to secrecy.

As shown above, scientists can choose between diverse platforms if they want to participate in open innovation. Usually you can register with detailed profiles. In most cases you can communicate with different experts within your fields of knowledge or interest. In this way, there are other advantages apart from the financial benefits in the event of winning a challenge: insights into a company’s internal problems are given that might also fit in with a scientist’s own range of duties.

It is apparent that there are a great many inspiring options and processes to be gained from the variety of platforms, which may play a substantial role in fostering the integration of and collaboration between scientists.

It will be exciting to watch and see how Marblar’s gamification principle develops and to find out if financial incentives are to remain the most important aspect of open innovation. But how do individuals, companies, scientists and experts respond to platforms like Inpama.com or Presans.com: will challengers/inititators prefer to submit challenges to platforms like Innocentive.com or do they accept the possibility of search engines browsing through the data of submitted technologies?

The legal aspect remains of considerable importance: Innocentive.com outlines the point of the challenge fairly clearly when intellectual property changes ownership. But still, details of that have to be discussed between the “solver” and the “seeker”.

Risks in Crowdsourcing Science

It is clear that different risks have to be taken into account when using or applying the methods of crowdsoucing or open innovation. The crowd is not invincible, although often praised for clustered intelligence. A high number of participants does not guarantee the finding of an ideal solution.

But who actually makes the final decision about the quality of the contributions in the end? Does it make sense to integrate laymen, customers or individuals and researchers who work outside the problem field into these kind of creative processes in any case?

A detailed and unambiguous briefing by the platform host seems to be called for. This also applies to participants: ideas need to be short and formulated clearly in order to survive the evaluation process. It is one thing for a company to ask its target group about marketing problems but quite another to ask the target audience—where only a few are professionals in the problem field—to solve difficult and complex (research) questions. Nevertheless, human tasks of different but less complexity can be carried out by anonymous carriers, although the limits are still reached fairly quickly.

Another important factor is dealing with the high number of submitted ideas and proposed solutions. Who should and might actually be able to evaluate them all? How does one avoid overlooking the best ideas? Often crowdsourcing also means that the participants themselves evaluate their proposals—in this way a form of pre-selection takes place and points out ideas that should attract interest. Nonetheless, manipulation may occur when networks or communities fuse to support certain ideas because they aim to win the prize, inflict damage on the initiator or for any other reasons. You can overcome this risk by backing up the crowdsourcing process with a jury of experts who monitor the process and can intervene and provide a final evaluation, where required.

There is always the risk of a participant losing his or her idea without getting paid for it. This might even happen without the initiator’s appearance: it is possible that other participants or external viewers steal the idea. In this context we have to mention that it is frequently only the winner who gets rewarded for his or her input —all the other participants miss out although they might have contributed several days of dedicated effort for the purpose of the challenge.

For contestants, crowdsourcing and open innovation are a very debatable source of income. The safeguarding of a contestant’s property is left to his or her own resources. Researchers should therefore check the agreement drawn up between them and the platform host to see whether intellectual property is covered properly. This can be ensured by documenting timestamps and with the help of a good community management through the platform host.

Of interest to both parties is the delicate question of profit participation: what happens if the creative director receives 1000 Euros for his or her idea but the company makes millions out of this idea? The question remains why a researcher or other collaborator should join in without any certainty that his or her contribution at any stage of the research / creation process is of value, whether it will be appreciated and adequately remunerated. [Anmerkung des Lektors: annealed = gehärtet bzw. geglüht z.B. bei der Stahlproduktion. jk]

So, the initiator and participant have to take a careful look at legal protection. Actually, this can prove to be quite easy: The initiator can set up the rules and the participant can decide, after having’ studied the rules, whether he or she agrees and wants to participate or not. A situation under constraint, such as financial dependence, is often rejected a priori. Assigning intermediaries can often serve to adjust a mismatch. The more specialized the task, the more weight rests with the expert or “solver”. Internet communication enables the solver to draw attention to unfair conditions: Both platform host and initiator are interested in retaining a good reputation; any possible future participants might be discouraged. Much depends on the question of how the Internet can be used to connect B2C or B2B companies, scientists or research institutions to target groups and how to receive desired opinions and ideas; but also how to integrate scientists in particular? How to ensure and achieve valid results? What legal, communicative, social factors need to be contemplated? And what further steps are there to mind after a crowdsourcing process? It would be unflattering if customers, scientists and creatives were motivated to participate but, after that, nothing happened or they weren’t mentioned in reports on the crowdsourcing process. That would only cause or aggravate frustration and that is something nobody needs.

Outlook: What the Future Might Bring

A possible future route for development might be hyper-specialization: “Breaking work previously done by one person into more specialized pieces done by several people” (Malone et al. 2011). This means that assignments that are normally carried out by one or only a few people can be divided into small sections by accessing a huge “crowd” of experts including researchers from all knowledge fields and task areas.

There is usually an inadequate number of hyper-specialists working for a company. Provided the transition between different steps of a working process is smooth, the final result might be of a higher quality. Here the following question arises: at what point would “stupid tasks” start to replace the highly specialized work, i.e. where experts are reduced to the level of a mental worker on the assembly line?

One possible result of open innovation’s success might also be the decline or disappearance of research and development departments or whole companies: to begin with, staff members would only be recruited from the crowd and only then for work on individual projects.

Another outcome might also be that the social media principle of user-generated content could be transferred to the area of media products: normal companies could be made redundant if the crowd develops products via crowdsourcing and produces and finances them via crowdfunding.

A further conceivable consequence might be the the global spread of the patent right’s reform: new solutions might not get off the ground if they violated still existing patents. The more the crowd prospers in creating inventions, developments and ideas, the more difficult is becomes to keep track and avoid duplicates in inventions. This raises the question of authorship: what happens to authorship if the submitted idea was created by modifying ideas put forward by the crowd’s comments? When does the individual become obsolete so that only the collective prevails? Do we begin to recognize the emergence of a future model where individuals are grouped and rearranged according to the ideas being shared and the resulting benefits? And to what extent will the open source trend increase or find its own level?

References

Baldwin, C.Y., 2010. When open architecture beats closed: The entrepreneurial use of architectural knowledge. In Massachusetts, USA: Harvard Business School.

Chesbrough, H.W., 2003. Open innovation: the new imperative for creating and profiting from technology, Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

Cooper, R.G. & Kleinschmidt, E.J., 1994. Perpektive. Third Generation New Product process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11, pp.3–14.

Dougherty, D. & Dunne, D.D., 2011. Digital Science and Knowledge Boundaries in Complex Innovation. Organization Science, 23(5), pp.1467–1484. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0700.

Ehn, P. & Kyng, M., 1987. The collective resource approach to systems design. In G. Bjerknes, P. Ehn, & M. Kyng, eds. Computers and democracy. Aldershot, England: Avebury, pp. 17–58.

Enkel, E., Gassmann, O. & Chesbrough, H., 2009. Open R&D and open innovation: exploring the phenomenon. R&D Management, 39(4), pp.311–316.

Friesike, S., Send, H. & Zuch, A.N., 2013. Participation in Online Co-Creation: Assessment and Review of Motivations. In unpublished work.

Gassmann, O., 2006. Opening up the innovation process: towards an agenda. R&D Management, 36(3), pp.223–228.

Hippel, von, E., 2005. Democratizing innovation. The evolving phenomenon of user innovation. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft, 55(1), p.63—78.

Hippel, von, E. & Krogh, von, G., 2003. Open Source Software and the “Private-Collective” Innovation Model: Issues for Organization Science. Organization Science, 14(2), pp.209–223. doi:10.1287/orsc.14.2.209.14992.

Howe, J., 2008. Crowdsourcing: why the power of the crowd is driving the future of business 1st ed., New York: Crown Business.

Kline, S.J. & Rosenberg, N., 1986. An Overview of Innovation. In R. Landau, ed. The Positive Sum Strategy. Washington, p. 275—305.

Lakhani, K.R., 2006. The core and the periphery in distributed and self-organizing innovation systems. Doctor’s Thesis. Cambridge, Massachussetts, USA: MIT Sloan School of Management.

Lakhani, K.R. et al., 2007. The value of openness in scientific problem. In Working Paper. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard Business School.

Laursen, K. & Salter, A., 2006. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, 27, p.131—150.

Lichtenthaler, U. & Lichtenthaler, E., 2009. A capability-based framework for open innovation: Complementing absorptive capacity. Journal of Management Studies, 46(8), p.1315—1338.

Malone, T.W., Laubacher, R.J. & Johns, T., 2011. The Big Idea: The Age of Hyperspecialization. Harvard Business Review, July-August 2011. Available at: http://hbr.org/2011/07/the-big-idea-the-age-of-hyperspecialization/ar/1.

Marks, P., 2012. Unused inventions get a crowdsourced creative spark. NewScientist Magazine, 2876. Available at: http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21528766.000-unused-inventions-get-a-crowdsourced-creative-spark.html.

Murray, F. & O’Mahony, S., 2007. Exploring the Foundations of Cumulative Innovation: Implications for Organization Science. Organization Science, 18(6), pp.1006–1021. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0325.

Nielsen, M.A., 2012. Reinventing discovery: the new era of networked science, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Schuler, D. & Namioka, A., 1993. Participatory design: principles and practices, Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Tapscott, D. & Williams, A.D., 2006. Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything, New York, USA: Portfolio.

Wessel, D., 2007. Prizes for Solutions to Problems Play Valuable Role in Innovation. The Wall Street Journal. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB116968486074286927-7z_a6JoHM_hf4kdePUFZEdJpAMI_20070201.html.

Human Genome Project Information:↩

Human Genome Project Information - About the Human Genome Project: http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/project/about.shtml↩

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Consortium: http://genome.ucsc.edu/ENCODE↩

National Human Genome Research Institute: http://www.genome.gov/10005107↩

Scientific American: http://www.scientificamerican.com/citizen-science↩

One Billion Minds: http://onebillionminds.com/start↩

Next chapter: The Social Factor of Open Science

Tobias Fries